That Was Quick (Go-Bag's Maiden Voyage) in Here Be Dust

- Jan. 15, 2016, 8:43 a.m.

- |

- Public

Four days after I posted my entry on my ER Go-Bag, I had to use it. Or, as one of my nurses put it, “That’s spooky.”

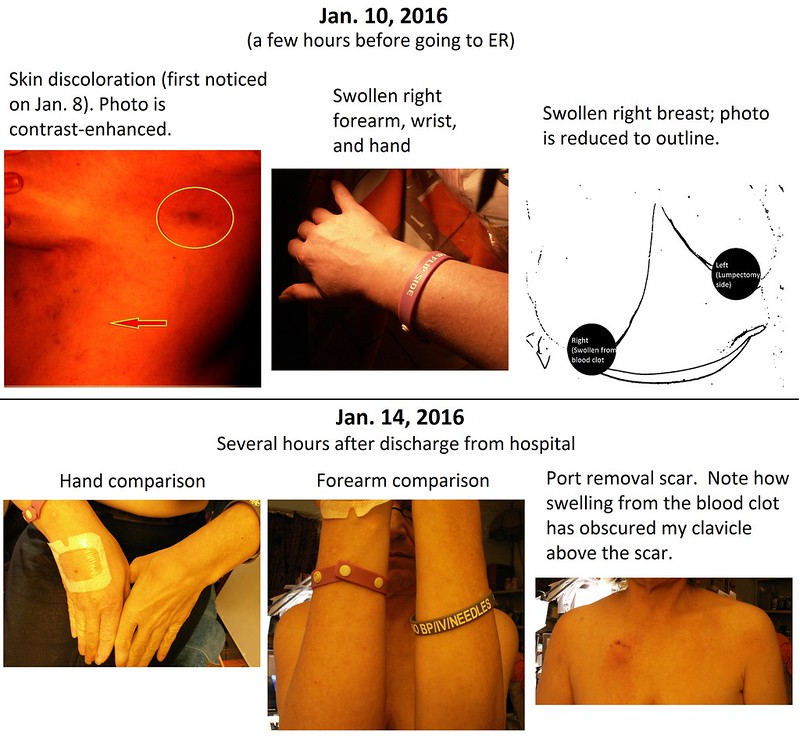

On Friday, two days after I posted the entry, I spotted a bruise-like skin discoloration on my right side, level with my breasts. It was about the size of a quarter but it wasn’t painful or tender. I figured I had inadvertently bumped into something and left it at that. Later on I noticed other skin discolorations on my torso, which looked more like stretch marks.

On Saturday I noticed that my right arm was swollen, down to my wrist and fingers. I had just finished a freelance job that involved some long hours (my most intense work session since before my diagnosis). Afterwards I had caught up on sleep, so I figured I had just slept on that arm and the swelling should go down. Mainly I felt pumped from the job, because it showed me that I still had my mojo.

By Saturday night the swelling had not gone down; it had increased. Also, my right breast was changing. I first noticed what looked like a dime-sized bump on my right areole and said, “WTF?” Immediately I performed a self-exam. My breast felt swollen, but nothing felt hard or hot. The bump resembled a mosquito bite. A few hours later it became a crease instead. Then the crease smoothed out. When I took a deep breath I felt mild soreness above and to the right of my port; otherwise I felt no pain or discomfort.

I resolved to call my oncologist first thing Monday morning unless everything cleared. If conditions worsened I would make an emergency call on Sunday. All of this was happening on my non-lumpectomy side. If my left arm looked the way my right arm did, I would have immediately suspected lymphedema.

However, my chemo port was on the right-hand side. I wondered if it might have sprung a leak.

I wrote in my journal, “Right now I feel a sense of stoicism mixed with concern – again I deal with the unknown, which for me is more frightening than the known…. Whatever it is, it is definitely something. And I don’t think this one is going to go away…. Body, what are you up to?”

By Sunday afternoon my right breast was considerably swollen in addition to my arm. I got on the horn and called my oncologist – who is out of the country until next week.

His colleague, covering for him, called me back. After hearing my symptoms and making sure I experienced no problem with my lungs, he said it might be a blood clot caused by the port. “You could go to the ER today,” he said, “or wait until Monday, come in, and we’ll do an ultrasound.”

I asked, “What would you do if it were you?”

He said, “I’d go to the ER.”

Time to grab the Go-Bag! Now with vitamins and energy bars added. At the last minute I also grabbed my “just in case” duffel with sleepwear, underwear, bathrobe, and extra toiletries, and threw that in the trunk. Good thing I did. My partner wanted to come with me, so we made sure that she also had what she needed (especially given her MS). More out of wishful thinking than anything else, I drove us in my car to the ER. My oncologist’s colleague called the hospital to warn them I was on my way.

I included that last bit of info on my ER registration sheet and brought it to the attention of the guy doing intake. Speaking up paid off. He’d had no idea I was coming. He said the ER doctor probably knew, but no one had informed the front desk. Before too long I was giving my info to the triage nurse. After a bit more waiting I was taken back for an ultrasound, where the tech spent a fair amount of time around my clavicle and jugular, then progressed down my arm. Periodically she switched to audio, in which my heartbeat did an imitation of a warp drive engine. At certain key points the tech pressed down on my skin, which sent the sound effects into hyperspace. If the monitor indicator were a seismograph, each finger push would be The Big One.

“No pitting,” she said. My skin bounced back, leaving no indentations.

My partner and I returned to the waiting area. A few minutes later I was put into a wheelchair and pushed toward the triage beds.

A registration nurse called out, “I’ve got her next!”

I piped up, “I’m popular!” Next thing I knew I was wearing a robe and lying in Treatment Bed 18, while a nurse/tech hooked me up to a heart monitor. The pulse ox monitor on my left index finger glowed at its tip. I said, “I feel like E.T.”

My left arm is at lifetime lymphedema risk, meaning it should get no needles of any kind and no blood pressure cuffs. Normally we use my right arm for those. But my right arm was swollen, so it was also off-limits. The BP cuff went on my right leg.

First reading: 150-something over 60-something. My diastolic (pressure between heartbeats) was its usual self, but my systolic (pressure during heartbeats) had jumped 60 points above my usual (and fairly low) reading. It would measure 130-something later in the night.

The ER doctor stopped by to tell me I wasn’t going home anytime soon. As suspected, I had a blood clot, specifically DVT: deep vein thrombosis.

My GP’s colleague stopped by to get info from me. When was my last chemo? (October 16, 2014.) When was my port last accessed? (Early November of last year. “Probably November second,” I said, but admitted I wasn’t sure; turns out it had been the tenth.) I forget what other details I gave him, but he was impressed that I could.

There was talk of hooking me up to an IV of Heperin and Coumadin, the standard-of-care blood thinners used in these cases – except that both my arms were off-limits to needles. So was my port, which was too close to the clot. My right hand became our pincushion. Into the center of the back of that hand went an IV catheter, from which the first nurse tried to draw blood.

My blood (or vein) had other ideas. After a few pitiful dribbles, that vial was relegated to discard and a butterfly needle next hit the vein near my thumb. The second nurse succeeded there, filling a blue top vial – the kind that has to be filled all the way to the top.

Both nurses apologized for causing me pain. I said, “Hey, I’ve been through chemo and radiation. This is nothing.” I meant it, too; relatively speaking, it really wasn’t all that bad. With IV Heperin and Coumadin out of the picture, I was given two shots to the stomach of Lovenox, a blood thinner usually given to patients undergoing things like hip- and knee-replacement surgery. Later they would get hold of the one-shot dosage I needed. Days later, my oncologist’s assistant would tell me that Lovenox is low-weight molecular Heperin and the right choice for my situation.

My partner went to get my duffel bag from the trunk. She has mobility issues, not only from MS but also from her foot surgery last year. She arrived back at my ER bed in her own wheelchair, the duffel on her lap. She drove my car home that night.

I mentioned to the ER doctor that I had info from my most recent blood work and scans, but he was interested only in the readings they were taking. The registration nurse told me that even with my POA and Living Will/health care proxy on file at the hospital, these days they ask to see paper copies. I had them with me in my Go Bag and was ready to pull them out, but no one actually ever asked to see them during my stay. Go figure.

While I waited to be admitted I touched base with a friend and fellow breast cancer survivor, who let my Facebook friends know what was happening. Before leaving home I had left an update that I was headed to the ER. The hospital has WiFi, but my cell is a dumbphone and my laptop stayed at home.

Eventually I was moved to Room 312, Bed 2, but I wasn’t allowed to enter it (full bladder or no) until I had been weighed. The collection of fluid in my arm and breast had added a couple of pounds to what I’m used to. Bed 1 was unoccupied; for most of my stay I had a private room right across the hall from the nurse’s station. When I told the assessment nurse about my allergic reaction to Amoxicillin (and therefore my presumed allergy to drugs in the penicillin family), she said that Keflex and Ancef are also related to penicillin. Good to know.

The food service had closed and I had left the house before dinner. I was able to get a late snack of turkey sandwich, applesauce, chicken noodle soup, honey graham crackers, and saltines.

Assessment Nurse told me that I would get anastrazole in the morning, but I normally take mine at around midnight. That gave her computer a fit; the pill schedule couldn’t be changed until the next day. Fortunately, I had stashed three of my own pills in my Go Bag, so I took from my supply at the accustomed time, witnessed by the nurse. That way, when the day nurse tried to give me anastrazole at 9 a.m. on Monday, I explained to her that I had already taken it. By that time my dosing schedule had been changed to “bedtime.”

My earplugs also came in handy. So, too, my thermals and bathrobe from my duffel bag.

My next blood draw was taken from the front of my wrist, the one after that from the hollow between ring finger and pinky. My right hand became a tangle of gauze and tape surrounding an IV catheter that would eventually be used to administer anesthesia for my port removal.

My GP stopped by on Monday morning and told me to check with my insurer to see if it would cover Xarelto, a pricey little number that also thinned blood. In addition to the Lovenox I was being given a daily Coumadin pill in the hospital. Using Coumadin pills would involve a longer hospital stay and require regular blood tests for at least a couple of months once I was discharged (more like six months, my oncologist’s assistant said). As of that particular hour of the day, I had not yet met my deductible. Still, all things considered, I decided to go with the Xarelto and gave my GP the go-ahead.

Then the hospital’s financial person stopped by, to tell me that I had been placed on observation status. Observation status is a problem, a loophole that allows hospitals to charge patients for what should by all rights be covered as an inpatient stay. However, this is typically done with Medicare patients. I am not on Medicare; I hold private insurance. Getting hold of the records of my stay (including patient flowsheets) is also on my To Do list. I’m a great believer in paper trails, especially in situations like these. First item of business: Speak to my insurance representative once I got home.

My e-reader had enough juice to last me through my stay, but I had neglected to charge my mp3 player and didn’t have a charger with me. No biggie (but a good reminder to me to be better prepared). My GP had told me that I could walk about and get in a little activity, so I spent some time dancing by my bed. The music in my head was good enough.

I also called one of my clients, since I was in the middle of a job when all of this hit. Fortunately, my few days’ delay was not a problem.

The medical team wanted to keep track of my pee and poop. I had honed my number crunching of bodily functions during chemo. When I reported poop, I also provided the Bristol Stool Scale number. Much more frequently I reported when and how many milliliters I had pissed into the hat, while a nurse or CNA fished out a pad and took down the info, looking for the moment like wait staff taking a drink order. Or they entered the numbers into their medical station-on-wheels, which they brought into the room for administering pills, shots, BP, and blood tests. By the time I was discharged I had passed 1.1 gallons of urine. (Is that a 1.1-gallon hat in the toilet or are you happy to see me go?)

My surgeon stopped by on Monday to let me know that my port would be removed on Tuesday, time TBD because I was being shoehorned in. Port removal normally occurs in the office setting, but I was already in the hospital and under their jurisdiction. Any food and liquid consumption had to stop at midnight. I wrote a note on a paper towel asking that any delivered meals be left in my room for me to have when I returned from the OR, but food service already knew not to prepare anything for me until they got the go-ahead. Meanwhile, I tanked up before midnight, taking advantage of another turkey sandwich with applesauce and honey grahams.

The LCSW from my radiation center visited and posted the next update on my Facebook page. It was great to see her.

My partner and I kept in touch by phone. She had her own medical appointments and errands to attend to. In the past I’ve done those errands and have driven her to her appointments. She managed fine on her own, though things got a bit adventurous at times.

On Tuesday morning I learned that my port removal was scheduled for 2 p.m.; the prohibition on eating and drinking after midnight still held, in case they could move me up earlier. They did, by about two hours. My bed was removed from its power supply and wheeled through the hospital maze, to pre-op. I later noticed that the model of the bed was “Eleganza,” which I found highly amusing.

Pre-op was Grand Central Station. The challenges my situation presented were small potatoes next to the people in beds to either side of me. We were all separated from each other by curtains, but my bed apparently occupied a central location. There was so little room for the staff to move around that I thought of the stateroom scene from A Night at the Opera, except without the comedy.

“You can see everything from where you are,” a nurse told me. (Well, I couldn’t see through the curtains.) “It only looks chaotic,” she continued. “We really do know what we’re doing.” Above and behind her a monitor tuned to the C.A.R.E. (Continuous Ambient Relaxation Environment) Channel showed bucolic scenes that belied what was happening in the room.

The anesthesiologist asked me the usual slew of medical history questions. The anesthesiology assistant looked like he hadn’t graduated high school yet, but he gave me what he called “happy juice.” Finally the IV catheter on the back of my hand was getting some use. My surgeon arrived to check up on me. He was still in his street clothes when he first entered the room, and I overheard his colleagues greet him with, “Happy Birthday!” While still conscious I added my good wishes to the chorus.

The next thing I knew, I was in the recovery room, and then my room. I was famished. My nurse arrived with my Coumadin pill. Dinner wouldn’t come for about five hours, but at least now I could have water. My surgeon stopped by before I could finish a makeshift birthday card that I would give him the next day. I had hoped that I could keep my port as a souvenir, but it had to go to pathology instead. Prior to surgery I had asked him if my blood clot could pose any risk of complication and had been told that it was possible, but rare. Now my surgeon reported back that the port had come out with no problem at all. As for the clot, most likely it had been caused by irritation from the catheter at the junction of my subclavian vein and my internal jugular vein:

I asked if my right arm now had lymphedema. No, he said. This is venous swelling. It should eventually go down. After he left I received a wonderful call from a friend.

A couple of hours later I felt a tickle. My IV needle had slipped out and was waving in the air, while rivulets of watery blood ran across and down my hand and onto my gown and sheet. “Uh oh.” I quickly repositioned my right hand and grabbed the call button with my left.

The dispatcher’s voice said, “How can I help you?”

“Hi,” I said. “I’m bleeding onto your floor and making a mess.”

“I’ll send V right over.”

While I waited I watched my bright red splatters, fascinated. If only I could take a picture and manipulate it into some kind of art piece. But my camera was at home, and if it were with me I’d only muck it up. Blood dribbled from my puncture like a tiny red artesian well.

V, my nurse that day, had given me my pill about an hour earlier. I smiled at him when he arrived and said, “The Coumadin works!” He put me back together as someone else toweled the floor and gave me a replacement gown. Only a couple of drops had reached the sheet, which would get changed out later. Housekeeping would put the finishing touches on the mop-up.

My dinner finally arrived at around 7:30 p.m., and I ate for the first time in 19-1/2 hours. Tossed salad, garlic roll, chicken parm, penne with marinara, roasted vegetables, and a brownie with strawberry for dessert. I inhaled it and followed up a bit later with the turkey sandwich combo from the after-hours snack supplies. During the rest of the evening I inhaled from a Voldyne 5000, which I was told was a precaution against pneumonia after surgery. I had to take at least 10 breaths per hour, raising the plunger to 2500 ml of inspired volume.

It made me think of a Coney Island boardwalk arcade game from my childhood – the one where my father could always aim a water pistol stream to raise a little yellow ball in a clear tube, high enough to ring a bell and win a goldfish. We’d spent happy summers flushing overfed carp down the toilet. In my hospital room, I was breathing for goldfish.

At around 8:30 p.m. my roommate arrived. At around 3:15 a.m. on Wednesday we were both laughing (she through considerable pain). First she went through her spiel to her nurse. Then it was my turn, because each shift brought a new nurse into service. Again I was explaining why we couldn’t use my left arm and why we couldn’t use my right arm.

From behind the curtain my roomie said, “It’s like we’re from the Island of Misfit Toys.”

In the morning my GP would be perturbed that no one had called her after my surgery, because she had been ready to give her discharge authorization on Tuesday. But by the time I finally left on Wednesday afternoon, my roommate and I had bonded and exchanged contact info.

My surgeon also stopped by on Wednesday. By that time I had completed my ditty-on-paper-towel and handed him my makeshift card:

I wish for you on this fine day

To get your birthday wishes

And thank you for the skillful way

That you’ve kept me in stitches.

I’ve had a lovely port of call,

Am once more setting sail.

You’ve helped me navigate it all

And always, without fail,

With grace, good humor, and a smile,

Compassion, joie de vivre,

And excellence, and extra mile.

So, may your birthday ever be

The best!

In appreciation – Elissa

It broadened the smile on his face. I’ll see him for a follow-up appointment in a couple of weeks. Already scheduled that week is my regular follow-up with my radiation oncologist. Next week I follow up with my GP and my medical oncologist, who should be back from his travels. In the meantime, I’m not to do any heavy lifting or anything straining my arms for about six weeks, though aerobic exercise is otherwise not only allowed but encouraged.

Another of my oncologist’s colleagues also stopped by on Wednesday (a different oncologist had come on Tuesday, while I was in the OR). I raised the issue of port flushing frequency, which has no clear standard; I had also raised it in the past with my oncologist. Most reports I’ve seen describe port flushes occurring anywhere from a month to eight weeks apart. My oncologist recommends port flushing every three months. On Wednesday his colleague cited a study (the citation of which I forget) backing that up. My clot had occurred 8-1/2 weeks after my port had been flushed, which the visiting oncologist chalked up to “bad luck.” He also said that if my swelling isn’t down in about five days, I should speak to my oncologist about getting a compression garment. (Ironically, I have a “just in case” compression garment for my left arm and hand.)

The day after discharge, when I made my oncology appointment, my oncologist’s assistant said that the type of blood clot I had was rare as far as ports are concerned. (“You’re special,” he told me. “I know that,” I said.) He added that my aerobic exercise habits have helped me considerably, both by making my symptoms more visible and by helping my body contain the clot.

Several nurses said they knew that I’d been chomping at the bit to leave the hospital “ever since Monday.” Finally, G, my nurse for that day, came with my discharge papers. I called my partner on the phone to give her the good news and to wait for her to come and drive me home. By this time my BP had fallen to a systolic of 120-something down to a shade over 100, while my diastolic continued to hold at 60-something. While waiting for my partner I enjoyed a 20-minute stroll around and around and around the hospital floor.

My Xarelto came via S (bedside Rx extraordinaire) at no charge thanks to manufacturer coupon magic and her juggling of two smartphones. She’d made the extra effort after the supply prescribed was twice what I expected, since my GP wants me to take two pills per day rather than one.

I spent part of the day after discharge making my appointments and checking in with my insurer, who said that I will receive a refund for the charges I had paid while in the hospital. My insurance rep told me that anything over 24 hours is considered inpatient and not “observation.”

I was also given a heads-up that a claim had been submitted by the doctor covering for my GP (this other doctor had visited me in the ER), whom my insurer won’t pay. I need to work that out with my GP. I suspect the same situation may also apply to the oncologist who had seen me, covering for my regular oncologist.

My hospital offers a 20% “prompt payment discount” for bills paid prior to discharge, which is why I had given them anything in the first place.

As long as my refund comes through, I would do what I did again:

1. Hand over my plastic early to get the discount, just in case insurance really didn’t cover that particular situation.

2. Check with my insurer ASAP, having available my general charge letter and receipts.

3. Follow up on any info provided by the insurer, such as the claims of doctors subbing for my regular ones.

4. If necessary, follow up to make sure my refund arrives.

As per my GP’s instructions, I now sleep with my right arm raised. Before my lumpectomy I had bought a body pillow so that I could keep my left arm raised and to keep me from rolling onto it. Now it’s my right arm’s turn.

I am thrilled to sleep again in my own bed. After getting home, it also took me a moment to realize that I don’t have to measure how much I’ve peed into a hat.

Then I logged onto Facebook and was floored by the best cheering section in the world.

Last updated February 05, 2016

Loading comments...