A birthday, a tooth, and three outworld gallivants in The Amalgamated Aggromulator

- Aug. 9, 2015, 10:42 p.m.

- |

- Public

Four days ago I finished a very strange month-long stint of editing. No thickets of narrow decisions are in my face. This will probably only last a few more days, but my free time is for the moment no longer a matter of either girding myself for the day’s rigid slog or reeling around in the post-edit state that resembles drunkenness. Three days ago I had an unplanned nap. Hie thee hither, and I will tell thee of the glories of the Unplanned Nap.

August 7th was my birthday.

Forty-eight. The final denial line of “closer to ___ than to 50” has been crossed. By the time I reach fifty I will be fully accustomed to it. (Anyway, to me 50 has had fewer doom-trumpets in it than 40 did. 40 always sounded like “the Flabby Forties,” the last dismal denouement of the feeling of being in early middle age. I did not enjoy the loss of 39. The fifties, on the other hand, have always sounded hale and hearty. Hirsute. Hemingwayesque. I don’t know why. And indeed it doesn’t matter why, these notions are mental upholstery. To whatever extent I must inhabit the role, I guess I’m approaching the task in a decent mood.) :-)

Though, somewhat related:

Yesterday I lost a tooth. It has been in the back of the top left side of my mouth, a molar, and it’s been loose for almost a year. I’ve been negotiating with it, biting gently down and pressing it back into place (this did work in the case of a different slightly loose one on the opposite side of my mouth, which recemented itself nicely), and have been rewarded only by increasing failure, with occasional minor interludes of quiescence, and an ongoing occasional mouthful of bright or torpid blood and a taste like the smell of old socks whenever I sucked at the spot. That’s where in past years there has been an abscess, and once a root canal - the odds just weren’t with me, and hadn’t been for some time before it started to loosen; I guess there had just been a little crucible of bacteria and bone loss right down in that spot. And in the last week it has been leaning more and more crazily, from side to side and back toward where my wisdom tooth used to be - and then, in the middle of a meal, floop, suddenly it was kicking around loose in my mouth. The psychological separation was fascinatingly instantaneous. It went all at once from being something I had been quietly, desperately loath to part with to being this strange coraline object that I had no desire whatsoever to put back. I wonder if the moment of death might be like that.

My mouth is fresh again. And my strongest immediate reaction was: I can finally try a flotation tank, next time I have money! The loose tooth has been the reason why I didn’t think I could before. In the absence of any other sensory input, I could imagine that cursed clicking, wobbly, moves-with-tongue tooth expanding to become my whole universe.

But I hope there isn’t more tooth trouble, or if there is I hope it comes slowly. Brush, Alex, brush. Or else (while I’m thinking of nonsense stereotypes for life decades) my entry into my sixties may be rather picturesque.

There has been a lot going on in the last couple of months, and a lot of it has had to do with the solar system.

I’d already had some idea of the situation - reading rare articles, and looking unhappily at the place through Google Earth - but this YouTube video startled me into a new period of mourning for my childhood town, Woomera, South Australia, which has had whole quadrants of its houses carted off to Roxby Downs (even the buildings for the elementary school are gone - I’m impressed, those were permanent buildings; how do you even do that?), and which has been reduced to a permanent population of about two hundred people, caretakers and their support, clustered in one little area. The rest of the village is kept intact but empty, it hovers in ghostly suspended animation against need, and I love the poetry of that - and, in one sense, the town of my childhood has certainly physically survived better than virtually anyone else’s for that reason . . . but the idea of the town, or the dream of the idea . . .

While I was in this mood about Woomera, several other, quite separate powerful frustrations bolted together with it to create a new mad obsession. For just a little while, I knew exactly what Australia should do.

I laid it all out in a couple of extended emails to an indulgent friend in Australia, who fortunately took it more as a charming “madness of King George” than as presumptuous meddling from a post/neo-colonial American George. (During this exchange I found out about the cuts to CSIRO - which nearly put me in a coma.)

. . . You know, I don’t think I’ll just summarize this here. I’ll wait and actually format and paste in the emails to make a separate entry. Some things are loves, wild loves, and it kills something in you to write only short summaries noting them (yas, yas) while the real things are consigned to fading.

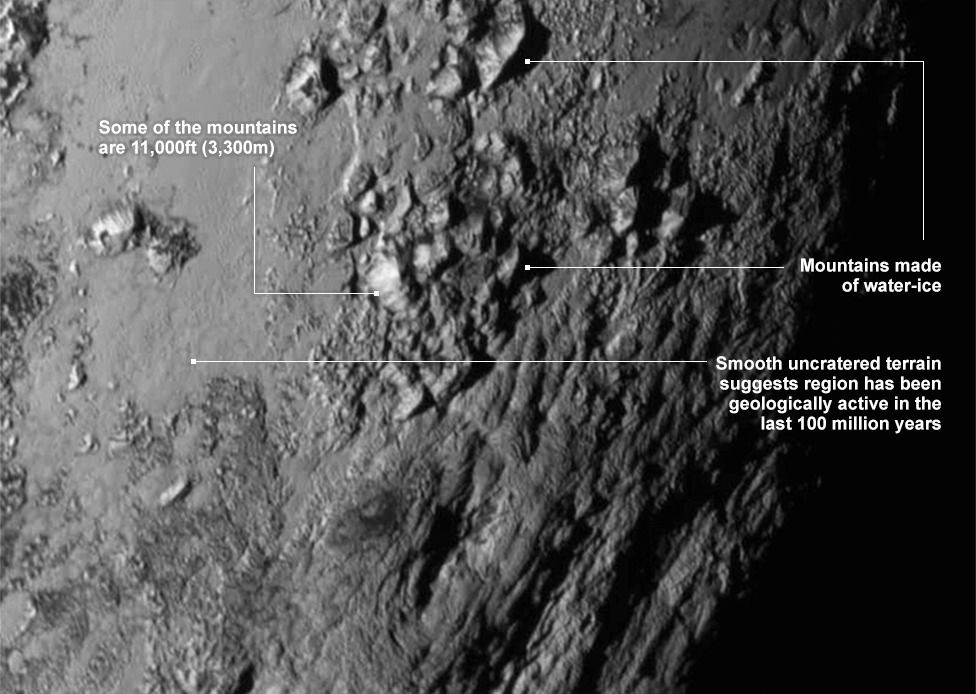

And then there was Pluto!

I had actually been expecting the Pluto flyby to be somewhat boring - or, not boring, but “the wonders of science! finally we have actual photographs of the iceball that we knew was there.” It was not that.

Reading about the first pictures got me very high.

New mysteries. Not just scientists excited to confirm standing theories or to see new forms of known phenomena - scientists dumbfounded. We don’t know it all yet. We can still get BIG surprises. The frontier is not closed.

This is a good article “of the moment” - complete with planetary scientists actually gibbering in the comments.

The other thing involved Jupiter. It was an enjoyable interlude in which I displayed my ignorance (and it did indeed prove to be genuine ignorance) and then successfully hunted down the problem.

Randall Munroe, who writes/draws the webcomic xkcd, also has a What If? blog in which people ask him questions about outlandish physical and mathematical situations and he describes how they would work. His science is invariably impeccable. Which mightily puzzled me when I ran into this sentence midway through a post:

There’s a point in Jupiter’s atmosphere where the pressure is equal to a little more than an Earth atmosphere—which is the pressure a submarine is used to—but the air there is barely a tenth as dense as ours.

I jerked to a halt and stared at it. I re-read it.

Huh?

How would that be possible?

How would a tenth of much atmosphere per cm3 press that much more per amount of air?

(Or: Why wouldn’t the gravity-driven pressure compact the gas to the same extent?)

Was it a question of different gases? Was the pressure some sort of distributed-molecule-velocity thing with less-dense gas in a much thicker layer (I typed this in Facebook, not quite knowing what I meant by the sentence - this was feel-around thinking)? I half-wrote about three other guesses and discarded them.

If that sentence was true, my confusion had the feel of a fundamental I was entirely missing. But a fundamental of what sort?

So I posted the question on Facebook.

A couple of friends from college who were good candidates for being able to answer it didn’t quite do so. (Not their fault; I think they just didn’t spend time on the question.) One typed in the ideal gas equation. The other referred to the equation and said that the answer seemed as if it would have to be a matter of high temperatures - which especially confused him because he had been thinking so much about Pluto he thought I was talking about Pluto’s atmosphere. :-)

Yes, I’d gotten the same thing from the equation - the answer seemed like it would have to involve high temperatures. As when you heat the gas inside a sealed container.

But . . . wasn’t Jupiter’s atmosphere cold? I was pretty sure it was.

In the back of my mind was the suspicion that Munroe had simply goofed. What was nagging me was that the sentence was kind of an odd tangent for Munroe. He didn’t need to say it. The question he was answering was whether there is a particular depth in Jupiter’s atmosphere at which a submarine would be able to float. What the rest of his piece explains is that whether a submarine floats depends on density, not on pressure, and that a submarine floats in water because the density of water, or of a liquid, is much, much greater than the density of a gaseous atmosphere (unless the pressure/temperature conditions are the impossible, submarine-destroying ones way down murderously deep in Jupiter).

So the observation in this sentence was a passing thought, a side blurp… and, from my own experience, “Homer nods” much more easily in side blurps.

But I wasn’t sure. Munroe is very good about stuff like this . . .

So I went Googling to hunt the thing down.

And I found this. From my notes:

Jupiter:

The temperature at the 1-bar level is approximately 165 K.

The density at 1 bar is 160 g/m3.Earth:

At sea level, standard air pressure is 1 bar.

At sea level and 15 degrees C (288.15 K), air has an approx. density

of 1.225 kg/m3, or 1225 g/m3.So, it’s true, and it’s definitely not due to higher temperatures

at the 1-bar level on Jupiter. Jupiter is colder at that level.

It had to be a matter of the different gases, or else I was out of ideas.

I went Googling further - and found a mathematical relationship that involved particular gases.

From my notes:

The equation is density = (pressure in bars) / (specific gas constant J/kg.K x temp K)

I went and looked up the gas constants, using hydrogen for

Jupiter and nitrogen for Earth.

The specific gas constants: (ideal gas constant / molar mass)

hydrogen = 4124 J/kg.K

nitrogen = 296.8 J/kg.K

I tried these in the equation with 1 bar for both and with

the temperatures I found,

and, sure enough, Jupiter’s atmospheric density at 1 bar is

around a tenth as dense as Earth’s, or more like an eighth,

which jibes with the figures I found.Blame hydrogen.

So that was the answer. I put it in Facebook in a comment under my post.

But did I understand why it was the answer? I worried about this. Why did it work like that?

Let’s see. Teeny little hydrogen atoms . . . Helium’s gas constant is also huge but smaller, so . . . Hmm.

Teeny little hydrogen atoms with small-diameter outer electron shells . . . was that it? . . . Or, teeny little light hydrogen atoms . . .

ONLY THEN DID IT FINALLY OCCUR TO ME THAT DENSITY IS NOT DEFINED AS THINGS PER UNIT SPACE, IT’S MASS PER UNIT SPACE!

(And even the molar mass part of the “specific gas constant” definition hadn’t dropped the penny for me!)

I had definitely taken the @#$%& long way around.

(And very soon a third friend commented and gave me the same thing explained much more pithily:

“Simple version: a bucket full of golf balls weighs more than a bucket full of ping pong balls. Density is a function of mass and volume. Pressure is a measure of ‘crowding’.”

I’d had the “crowding” muddled between the two words/concepts.)

Sure enough, a fundamental had been escaping me - and I had displayed my plain ignorance for all to see, to a greater degree than I’d have planned.

But I’m much prouder than I would have been had I not displayed it. I noticed and defined my confusion, and then I tracked the thing to its lair. Brain messy, but functional. :-)

Last updated August 10, 2015